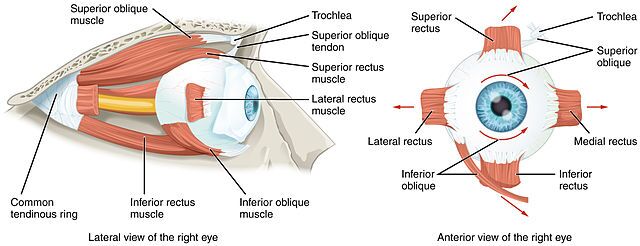

Many parts of the brain control the movements of the eyes (known as oculomotor control) through six muscles on each eyeball.

The electrical impulses from the brain to the muscles of the eyes make the eyeballs move extremely fast from one position to another (in split-second movements called saccades), very slowly (called smooth pursuit), or converge inward or outward slightly to focus on an object or word depending on how close or far away that word or object is from you (called vergence).

Numerous parts of the brain contribute to voluntary and involuntary eye movements, including the frontal, parietal, and occipital lobes, the cerebellum, as well as the midbrain, brainstem, and vestibular nuclei. Damage from seizures, stroke, or surgical removal/disconnection of any one of these areas can cause problems with eye control.

Eye control and reading

Good eye control is necessary for many important skills, especially reading. When reading a line of text, our eyes follow a path across the page that is from left-to-right and top-to-bottom in languages like English and Spanish.

While we may think that this path is smooth, it is not. The eyes actually alternate between rapid forward movements called saccades and then stop to fixate on a word. And all this happens in split seconds!

Sometimes the eyes will look at the same word (refixate) several times or words are skipped entirely. Which words the eyes choose to look at next depends on the length of the upcoming words in the line of text. Our eyes tend to fixate on the longer words and skip over short words like and, if, and so.

If a child has poor eye movement control after surgery, following a line of text smoothly, or fixating on a word properly can be very difficult. The child may spend too much time – often unconsciously – trying to get the eyes to fixate on a word rather than getting the meaning of the word.

Because the child reads slowly due to poor eye movement control, the educator may think the child reads poorly. This is why educators should be cautious when assessing how fast a child reads – known as a fluency – because poor oculomotor control may be slowing down the child’s reading speed. Just allowing the child more time may be all the accommodation necessary.

Take a moment to watch this video to understand the importance of eye movements when reading.

Strabismus or “eye turning”

The eyes must work together accurately in order to form binocular vision. Binocular vision overlaps the different views from both eyes, providing the child with depth perception and keeps the scene in sharp focus.

Surgery often results in one or both eyes turning in, up, or out – a condition known as strabismus. When one eye looks one way, and the other in a different direction, the brain receives two different visual images.

This makes it impossible for the brain to form a single image, so the brain may ignore the image from the misaligned eye to avoid double vision. In a child, the brain may completely shut out visual input coming from the misaligned eye resulting in a reduction or total loss of vision in that eye known as amblyopia. This also affects the ability to have stereopsis or 3D vision.

For these reasons, children after surgery should be followed by an eye doctor who understands visual impairments caused by the brain, and how it affects the development and overall function of the child. Treatments to improve eye alignment include eye glasses, eye exercises, eye patching, prism glasses, and eye muscle surgery.

Next – Fields of vision